Robert Frank is a little like a kaleidoscope: when you look at his body of work, you see different things from different angles. To some, the 90-year old master who revolutionized photography with his famous series The Americans: the iconic and seminal series of images in which Frank was an ‘equal opportunity’ portrayer of every sub-section of society (Americans often like to observe that there isn’t the phrase “class system” in the USA, but Frank vehemently disproved this notion).

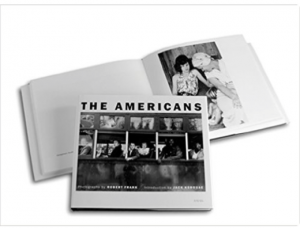

The series deviated so much from accepted ‘norms’ at the time (low-lighting, cropping unusual focus), that he had trouble finding a US publisher for the book. The Americans was, therefore, first published in Paris (but finally in 1959 is published by Grove Press in the US).

Over two years, he crisscrossed the country, amassing a body of more than 28,000 images in just about every state. It’s all here, from the diner to the ballroom, the north to the south, the happy to the dispossessed. It’s tribute to Frank that, in some ways, the body of work seems less ground-breaking now; but only because he set the new tone for every photographer that would follow him. His style is still evident in the compositions and concerns of contemporary work.

To some, he will always be a fixture of rock music history, when, in 1972: he was hired by the Rolling Stones to shoot the cover of their album Exile on Main Street. Frank also documented the Stones on tour in what became his notoriously infamous film Cocksucker Blues (so infamous, in fact, that it was never released. According to court order, the film can only be screened a few times a year with the artist present.).

To others, Frank will more familiar because of his radical shift into more abstract realms of photography and cinema.

Whatever your perspective, filmmaker Laura Israel has just made an intimate film portrait of his various manifestations in Don’t Blink – Robert Frank: a collation of the vast amount of artistic territory he’s covered: from The Americans in 1958, through to his own documentaries, his return to still images in the 1970s (he published his second photographic book, The Lines of My Hand, in 1972) up to the present day.

At 82-minutes, Don’t Blink is a compact and beguiling look at the mind of an artist unfettered by the notion of putting himself in any box or style.

Chief among Frank’s artistic attributes that Israel wanted to explore was his style of creation; which owes something to the bursts of energy exemplified by the artists of the Beat Generation with whom he’s sometimes grouped (Frank’s own filmic portrait of them, Pull My Daisy was narrated by Jack Kerouac).

As Israel states: “I was interested in sharing my insights into Robert’s relentless pursuit of creativity,” Israel explained. “He’s big on spontaneous intuition. I think that’s something that younger people could use a dose of, and that other people could be inspired by. The creative approach of, ‘I’m just going to go and do it. I’m going to do whatever comes to my head. I’m going to think about it but I’m not going to think about it too much.’”

The structure of Don’t Blink is in keeping with the roaming, creatively restless and aggressive nature of Frank’s body of work (and uninhibited artistic style): a back-an-forth journey traveling through various aspects of and periods in Frank’s life.

Israel’s own filmic perspective stems from Frank’s rule-breaking spirit, evident in first body of work. “I would like this film to be a stepping stone for people to understand where he went after The Americans, where he was going after that. You know, before The Americans journalistic photography was more about the captions than the photographs. You couldn’t have a photograph that said something striking in the image. His photographs didn’t need captions but also rather than trying to explain something they evoked a feeling.”

Don’t Blink – Robert Frank trailer from Laura Israel on Vimeo.